Hex House Mistress Bares Tragic Life

By Mary Louise Huff | Originally Published in The Tulsa Tribune on Wednesday, June 14, 1944

Death of Children, Suicide of Husband Broke Mind, Is Report.

Fraud Defense Indicated by Mrs. Carolann Smith's Story.

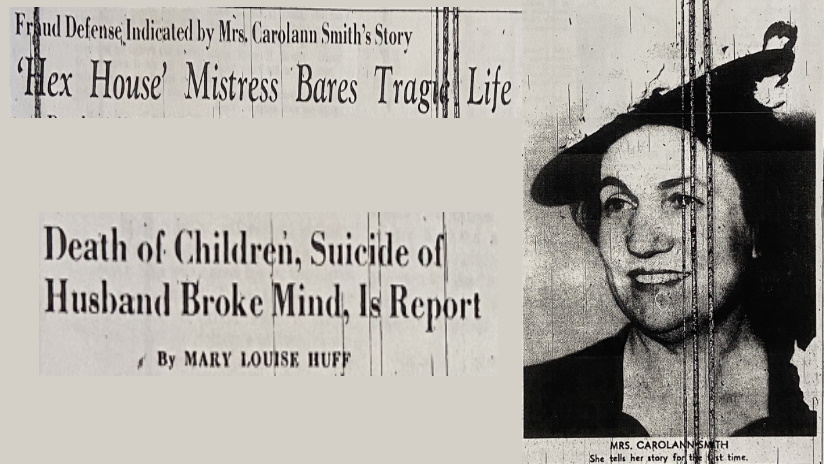

On the eve of her federal court trial on fraud charges, scheduled to start Friday in Vinita, Mrs. Carolann Smith, Tulsa's mysterious mistress of the "hex house" today lifted the stony mask she has worn through a series of court appearances and gave to the Tribune the story of her life.

She has been painted as a clever defrauder almost a witch in the stories which came from state witnesses and which to date she had never answered.

Talk to her a while and you'll find her refined, emotional, but utterly confused as though she's living through a bad dream. No matter what you've been lead to believe about her, you cannot help feeling pity if you believe her story.

When fitting Mrs. Smith's side into the picture presented by her two alleged "mesmerism" victims does not explain the unfathonable hex house situation, however.

Here is Mrs. Smith's story:

She was born 51 years ago in a suburb of Indianapolis. Her father, Thomas M. Carey, was with the pay roll department of the Indiana Glass Co. The Episcopalian family of English descent was well-to-do.

Her mother died when Carolann was 9 years old. The father never remarried, but reared Carolann and her two sisters. Carolann especially was devoted to him.

He was a prince, his daughter recalls. "He never left us a single night. He sent us to fine, private schools. I studied music."

In 1912 the father moved his brood of girls to Muskogee. There in 1914 21-year-old Carolann met Fay H. Smith, a salesman for several steel companies, and married him. Her wedding picture show her a slim, beautiful girl in a formal gown with a veil falling from her head to the floor.

Smith made a good income, and the couple were devoted, she says. The young wife had tender letters whenever her husband was on trips through his sales terroritory, frequent gifts, and almost everything she desired for her home.

That is, everything but children.

Mrs. Smith wept today as she tried to tell of the death of her two sons, born in Muskogee between 1915 and 1919. Both babies, born prematurely died a few hours after birth.

Doctors told Mrs. Smith she was not strong enough to have children. She had been in delicate health throughout early life. She seems not yet recovered from the grief of losing her children.

I still have the little things made for them, she sobbed.

Shortly thereafter, the Smiths moved to Tulsa, where the husband worked as a sales manager of the Williamsport Wire Rope Co., a subsidiary of the Bethlehem Steel Co. Except for short interludes when he was transferred to Casper, Wyo., and Portland, Ore., he was in Tulsa most of his life.

On June 30, 1933 at the height of the depression came a letter from C.M. Ballard, vice president of Williamsport Wire Rope.

It is necessary for the receivers of this company to dispense with your services, it read. "There isn't any one I care to see go less than you."

In January 1934 Fay Smith was found dead in his car in the Osage Hills, bullet wounds in his chest and his father's gun nearby. In the crown of his hat was a note directing the finders of his body to notify his wife.

Mrs. Smith suffered a nervous breakdown after her husband's death and was cared for in the home of a prominent Tulsa family. Her only close relatives were a sister, Mrs. Ethel A. Folger, and her father, who lived with Mr. and Mrs. Folger in Monahan, Texas. The other sister had died.

Mrs. Smith returned to her apartment in the Sophian Plaza and began making arrangements for her father to live with her.

But the father died in September 1934.

Mrs. Smith lived on at the Plaza. After loans were paid off, her husband's insurance gave her an income of around $140 a month. Friends encouraged the widow to again concentrate on her music, and she began taking voice and piano lessons at Tulsa university, planning to teach.

Meanwhile, however, she became physically and perhaps mentally ill. Although she had found some comfort in Christian Science after the death of her sons, between 1920 and 1924 she went to many local doctors for a long series of treatments from 1934 until now.

One of these, Dr. Howard A. Welch of Tulsa, will testify at Mrs. Smith's federal trial in Vinita. Here is his report on his patient, made May 16, 1944:

My diagnosis is psychasihernia or in other words, the connection between nervous disease and outspoken insanity.Mrs. Smith's phobias and mental weakness were typical. She was unable to think a problem through. She did things in a stare. She extremely suspectible to the influenced and suggestions of others.

From her talk and actions, one would think at times she was living in the a world foregin to ours.She shows evidence of the menopause, which renders the nervous system unstable. Basal metabolism shows hypothyroid. There is low functioning of the pituitary, spleen, and ovarian glands.

On numerious ocassions while at my office for treatment, Mrs. Smith would seemingly go to pieces, cry for some tome and become exhausted, both mentally and physically. She would them remain in bed for some time. She did not make a quick comeback mentally or physically.

Among the other doctors who have treated Mrs. Smith in the past few years here are Dr. V.K. Allen, Dr. Layne Perry, Dr. John K. Halladay, and Dr. Walter Larrabie. She had sepnt several months in the Kolac clinic Wichita, Chestnut Hill sanitarium at Brookline, Mass., and the Rebmeyer hospital in Monahan, Texas.

Dr. S. Charlton Shepard, Tulsa, now a lieutenant commander in the navy stationed at San Francisco, treated Mrs. Smith for glandular disturbances and nervousness until 1941 when he went into the service. His reports will be presented at her trial.

Also testifying will be Dr. Felix Adams, head of the Eastern Oklahoma hospital at Vinita, who has been examining the defendant for sanity on the order of Federal Judge Royce H. Savage. Doctor Adams' report will be filed soon.

With this information on Mrs. Smith's condition since the death of her husband and father, it is easier to understand the view she presents of the "hex house" where she lived with Virginia Evans and Willetta Horner.

Virginia moved into Mrs. Smith's Sophian Plaza apartment in 1937 after Mrs. W. A. Zellner Tulsa, recommended that Mrs. Smith use the Stroud girl in as a roomer.

I felt sorry for Virginia, Mrs. Smith explained today. "I always feel sorry for people. I'd knew my husband a few years before and Virginia had been divorced after three weeks of marriage. I thought our heartaches were similar.

Virginia was different from most girls. Mrs. Smith went on. "One evening, after she'd been with me about a month she confessed to me that she gone through all the drawers in my bedroom as well as the rest of the house. She had taken nothing, though. She seemed sorry and said she wasn't going to do it any more.

But she gradually barged in and took over the entire house, the accused woman went on. "She went to Stroud every weekend, but other times she had girls from her home town come up and they filled the whole place. I finally told I was not situated for her entertainment. I asked her to move, but she refused. I raised the rent to $10 in order to get her out, but after going home and talking with her father, she stayed on.

She told me she had never been hapy in her life. She wanted to lead a good life. I don't believe she went out with a man a single time during the seven years she lived with me. She seemed afraid to go.

When I'd ask her to leave she'd cry and beg to stay, insisiting she had no home nor husband.I met Willetta at a grocery story in 1938, and she came to see me often," Mrs. Smith went on. "She asked to move in. She told me she hated her home life and managed to escape through the help of a friend.

When working girls no longer were allowed to live at the Sophian Plaza, Willetta arranged for us to lease a house at 2503 S. Boston pl., and we moved in.The girls seemed to want a nice home. Willetta told me she wanted to be my daughter, and I felt like a sister toward Virginia. They ever turned over their pay checks to me. Willetta handled all our business affairs."

In 1940, Mrs. Smith made Virginia and Willetta beneficiaries of her husband's original $13,000 insurance policies. If she had died in jail in March, the girls would have benefited. The policies expired, however, on May 22, so far as the girls' benefits were concered.

According to Mrs. Smith, the home she attempted to set up for the two younger women soon became miserable for her.

Copyright Tulsa World. World Publishing Co. Rothline Entertainment provides this digital version of copyrighted material based on the copyright regulations for fair use. More information provided atcopyright.gov. This material is provided for the research of the events regarding the Mistress of the Hex House in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Rothline Entertainment also follows the copyright terms provided by the Tulsa World and those terms can be reviewed at Tulsa World Terms and Copyrights.

Contents

Mistress of the Hex House

- Body of Missing Tulsan is Found

- Police Jail Woman

- Insurance, Missing Casket

- Sinister Implications Seen

- Hex House Horrors

- Hex House Legacy

- Hex House Scandal

- Mistress Bares Tragic Life

- Hex House Spectators

- Tulsa Notorious

Bigoot Stories

- Awakened By Bigfoot

- Bigfoot Adair

- Bigfoot Arbuckle

- Bigfoot Atoka

- Bigfoot Braggs

- Bigfoot Bryan

- Bigfoot Catoosa

- Bigfoot Cherokee

- Bigfoot Choctaw

- Bigfoot Cleveland

- Bigfoot Colyer

- Bigfoot Encounter Crossett

- Bigfoot FBI

- Bigfoot Grand Lake

- El Reno Chicken Man

- Mountain Home Bigfoot

- Roadside Bigfoot

- Rogers County Bigfoot

- White River Bigfoot

- Wilburton Bigfoot Prowler